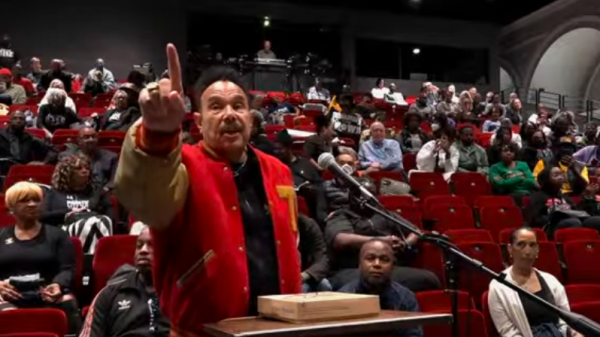

(This is an adaptation of a speech given at the Association for Private Enterprise Education meetings, April 16-18, 2023)

We find ourselves trying to navigate the surging rapids downstream from the confluence of three powerful currents.

The first is the great success of liberal institutions in creating prosperity. Dierdre McCloskey has rightly called this period of about two-and-a-half centuries, which is frankly unprecedented in human history, the “great enrichment.” But this success has made the proponents of classical liberalism complacent, even lazy. We did not anticipate that the astonishing burgeoning of prosperity would cause, in dialectical inevitability, a backlash against inequality. We have abdicated our essential role of explaining the moral case for capitalism and spontaneous, decentralized institutions, and the political left has rushed in to take advantage of the vacuum.

The effects can be seen everywhere, but perhaps nowhere more strongly than in Chile, where a dramatic increase from the economic middle-of-the-pack to continental preeminence has spurred a vicious and frighteningly effective campaign to undo all the “damage” that the left perceives in free institutions. My friend Ernesto Silva Mendez, and his newly created think tank Faro UDD, are facing an enormous challenge as the Chilean people consider a new Constitution, one that risks throwing away all the gains of the past 50 years. Chile is only a few years ahead of other democracies, however, as classical liberals pay the price of having been satisfied to make consequentialist arguments about prosperity, instead of doing the harder work of arguing that individual rights and personal responsibility are moral obligations that no state can legitimately transgress.

For much of the 20th century, citizens were willing to accept substantial inequalities as long as their own economic conditions were improving, and each successive generation could expect to be better off. But it appears that concern for inequality is what economists call a normal good, meaning that demand increases as income rises. Further, the immediate catalyst for unrest has been the very government programs that purported to “address” inequality, through higher taxes and constantly expanding regulation have throttled the increases in prosperity that fueled the bargain. We did not anticipate the negative feedback loop, where attempts to reduce inequality have reduced prosperity, calling for constant expansions in the political demands to reduce inequality.

The second great disruptive current is the rapid expansion and penetration of “social media” into many aspects of our political lives. The emotional pleadings of the economic left, and the superficial appeals of brazen identity politics, are able to reach nearly everyone — especially young people — unanswered by the logic of argument or the wisdom of experience. In fact, it is commonplace that the increased interest in socialism is a direct product of the near total lack of empirical lived experience with socialism’s manifest defects. “This time will be different” has been the mantra of every generation, and it was certainly the view of “my” people, the weirdly confident leftists of the 1960s. But at least that perspective was tempered by seeing the combination of poverty and dashed hopes of actual socialism, as the Soviet bloc alternated between bellicose bluster and economic entropy. In the current environment, the flood of memes and apparently profound (but actually empty) slogans overwhelms the laborious explanations and background needed to understand the value of liberty and voluntary exchange.

Finally, the third great current is the ideologically charged sentiment against the market system in general, and capitalism in particular, among the most recent crop of high school and undergraduate students. Those of us who work in academics have made, in my view, a fundamental strategic error by accepting a corrupt bargain. Many of our best and most effective thinkers, writers, and speakers have voluntarily isolated themselves in intellectual ghettos, and have consented, sometimes explicitly, to have little or no direct contact with students in mainstream courses, and no influence over what is taught in the majors that organize the US curriculum.

The reasons are understandable, but not very admirable. By accepting outside money and wanting control over what we teach and write, we have abdicated our role as a counterbalance toward the now-ascendant dogmas of the left. The craven desire to have “teaching relief” — that’s actually what professors call it, as if teaching were a headache, and having your own center were ibuprofen! — has self-relegated more of our people to the sidelines than any ideological discrimination by leftist administrators could ever have achieved.

Worse, far too few classical liberals are in positions where they can contribute as academic administrators, ranging from department chairs to deans to provosts, and be able to give an inside voice to the arguments for why education requires intellectual diversity. We have many allies on the left, people who actually care about education, but because we have accepted an easy life in a ghetto rather than a life of contention and debate in the main arena, those allies remain silent and ineffective.

The solution, the way to navigate the rapids downstream of where we are now, is clear, but not easy. It is to refocus on making the moral case for capitalism, on providing a positive, optimistic vision of the world that can be remade. That new world is a place where great enrichment is nurtured and expanded, and the increase in wealth, widely shared, is revivified.

We should perhaps take heart from the words of F.A. Hayek, who in 1949 was in an intellectual setting that was as bad, or even worse, than that in which we find ourselves today. He wrote, in “The Intellectuals and Socialism,” about how the failure of classical liberals to advocate for the good society had allowed socialism to gain a foothold, and then expand toward becoming dominant. Hayek put it this way, and his words are as powerful today as they were in 1949:

…we must be able to offer a new liberal programme which appeals to the imagination. We must make the building of a free society once more an intellectual adventure, a deed of courage. What we lack is a liberal Utopia…a truly liberal radicalism…the main lesson which the true liberal must learn from the success of the socialists is that it was their courage to be Utopian which gained them the support of the intellectuals….