A crumbling tribal school that was the subject of widespread community outcry is set to be replaced after Nevada Gov. Joe Lombardo signed into law funding for a new facility on Tuesday.

Flanked by tribal leaders and dozens of students who traveled to the state Capitol from a reservation in a remote swath of northern Nevada, Republican Gov. Joe Lombardo signed the legislation that funds both a new school and opens new mechanisms for tribal and rural school funding across the state.

‘I’m so proud of the youth for making these long trips, meeting with legislators and making this a true learning experience,’ said Brian Mason, chairman of the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Reservation.

The public Owyhee Combined School on the Duck Valley Indian Reservation hosts 330 students from pre-K through 12th grade along the Nevada-Idaho border. The Shoshone-Paiute Tribes on the reservation have about 2,000 members, nearly all of whom have attended the school built in 1953.

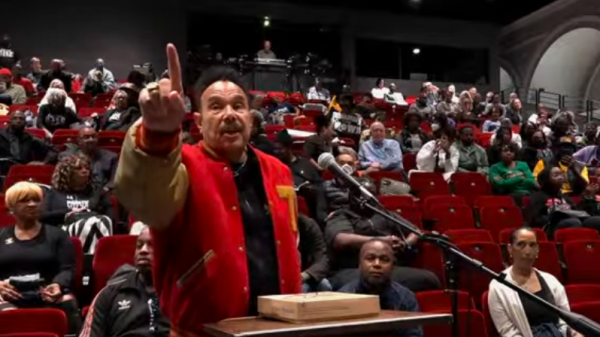

Hundreds of tribal members visited the Nevada Legislature in April, where they pleaded for new school funding.

They described a bat colony living in the ceiling, where drippings ebb into the home economics room. Stray bullet holes have remained in the front glass windows years after they appeared. The school is a stone’s throw from a highway, where passersby sometimes use the school bathroom as if it’s a rest stop.

Perhaps most hazardous is the school’s location, which sits adjacent to toxic hydrocarbon plumes that lie under the town. Tribal doctors are preparing a study in relation to a noticeable string of cancer deaths.

‘Our current facility, designed and built at a time of the policy of ‘kill the Indian and save the man,’ no longer serves us,’ said Vice Principal Lynn Manning-John at the bill signing. ‘For our future of our tribe, and for us as individuals, this new school promises hope.’

The new school will take about three years to build, Lombardo said.

Sponsored by Democratic Assemblywoman Daniele Monroe-Moreno, the bill allocates $64.5 million for a new Owyhee Combined School and also creates other funding mechanisms for other tribal and rural schools. Rural Elko County, which has jurisdiction over the Owyhee school, has just over a year to decide whether to pay an additional property tax for or divert part of its revenues for a school district capital fund.

The bill gives other rural counties’ board of commissioners the option to raise property taxes to help fund capital projects for schools on tribal land. It also creates an account of $25 million for capital projects for schools and another $25 million specifically for schools on tribal land.

One school that could benefit from the bill is Schurz Elementary School, on the Walker River Reservation in rural Mineral County. Walker River Paiute Tribe Chairwoman Andrea Martinez originally advocated for the bill when it only included the funding for the Owyhee School, but became more involved when it was widened to include more rural and tribal schools.

‘For our culture, we think about the next seven generations. And the people that put in the work to do this, that’s where their mindset is,’ Martinez said. ‘It makes me happy to see that’s where our mindset is now, instead of trying to just survive the systemic injustices we’ve been facing.’

Teresa Melendez, a tribal lobbyist and organizer who worked on the bill, said some tribal leaders and principals are considering a feasibility study to create a new tribal school district for a more cohesive funding and curriculum plan across Nevada’s four reservation-based schools. They would hope to have it done before the next legislative session in 2025.

‘These schools have been neglected for decades,’ Melendez said. ‘But it’s not just the facilities. We need solutions regarding the teacher shortage, the teacher housing issue, culturally insensitive and inaccurate curriculum. There’s a host of Indian education issues that we need to tackle.’

<!–>